Researchers' theory examines how weather may hold clues into the likelihood of shark attacks

Scientists believe shark attacks can be predicted based on certain weather patterns. ABC's Will Reeve goes shark tagging with two experts testing their revolutionary new theory on forecasting shark attacks.

As summer continues and many head to their favorite beach destination, shark sightings have become more frequent. While shark attacks are highly unlikely, they tend to be reported more during the summer months when there are more people in the water.

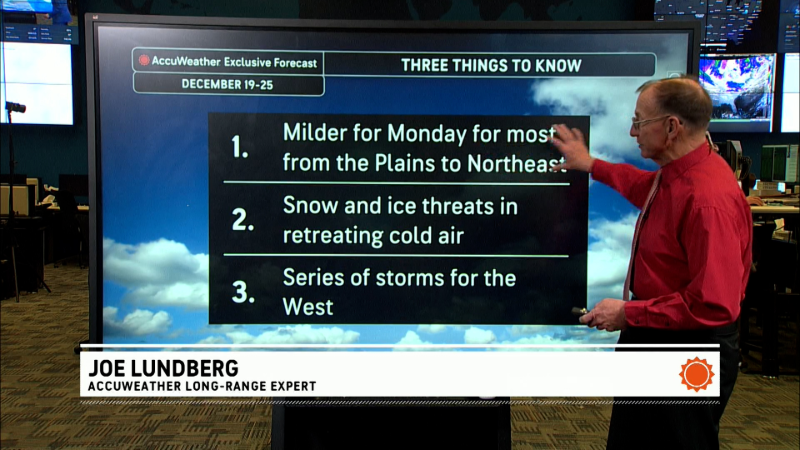

Many beachgoers understandably may want reassurance that the likelihood of a shark attack is very slim before they head into the ocean. Scientists have developed theories that they hope will better predict shark whereabouts and the likelihood of an attack. One of which was hypothesized by Joe Merchant, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service (NWS) office in Lubbock, Texas.

A few years ago, back in 2015, there were 10 official shark attacks off the coast of the Carolinas. Merchant took notice to this uptick in attacks and recognized that two of the attacks, which occurred within an hour of one another, occurred on a day where there was a really strong sea breeze.

Merchant said that while he watched the infamous shark attack movie "Jaws" when growing up, he never had a particularly strong interest in sharks. But after he noticed the connection between the shark attacks and the strong sea breeze, he wondered if there was a connection.

The Shallows, Gansbaai, Western Cape, SOUTH AFRICA (Bernard Dupont/Flickr)

Merchant contemplated this theory for some time, going back and forth on whether or not there may be some truth behind this idea.

“I finally decided that I was on to something,” Merchant told AccuWeather. “And so I contacted Dr. Greg Skomal, just cold called him.”

Merchant is originally from Massachusetts, where Skomal, a shark biologist, is a program manager at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries. The pair’s expertise brings together weather and sharks.

“Once we started talking and discussing all of the different factors that go into it, we started seeing a pattern, and we've been working together since,” Merchant said.

Merchant said that the convergence along the sea breeze front starts a predatory chain reaction in the food chain below the surface. The sea breeze brings nutrient-rich, deep water closer to the surface, attracting tiny marine life that feed on the nutrients. Those small creatures attract larger fish, which in turn attract the ocean's largest predators, sharks, who are on the hunt for prey. The sharks, therefore, come closer and closer to the shore where swimmers are located.

At the same time, sea breeze conditions and “pleasant” beach days typically go hand-in-hand, according to AccuWeather Meteorologist Brian Wimer. A sea breeze is more likely on a sunny, warm beach day.

“Sea breezes happen during the warm season during the day because the sun heats up the air over land faster than over water. The warmer air over land rises, and is replaced by air coming inland from the ocean. This occurs mainly from late morning through the afternoon. The process is typically reversed at night, as the air over land cools faster than over water,” Wimer explained.

And would the average beachgoer recognize that there is a sea breeze?

“Yes, depending on how big a difference the temperature is between the land and water,” Wimer said. “In some cases the wind is strong enough that an average person would consider it windy. And the wind can cause blowing sand.”

However, the beachgoer may not recognize the wind as a sea breeze. They would, however, notice that there was more wind than earlier in the day and that it was blowing in from the ocean.

Merchant and Skomal’s theory could help create a better understanding of shark behavior and the likelihood of attacks.

"If we can use the weather to indicate what sharks are doing, we might be able to predict whether or not a shark attack will occur, and that would be absolutely amazing," Skomal said in a National Geographic documentary.

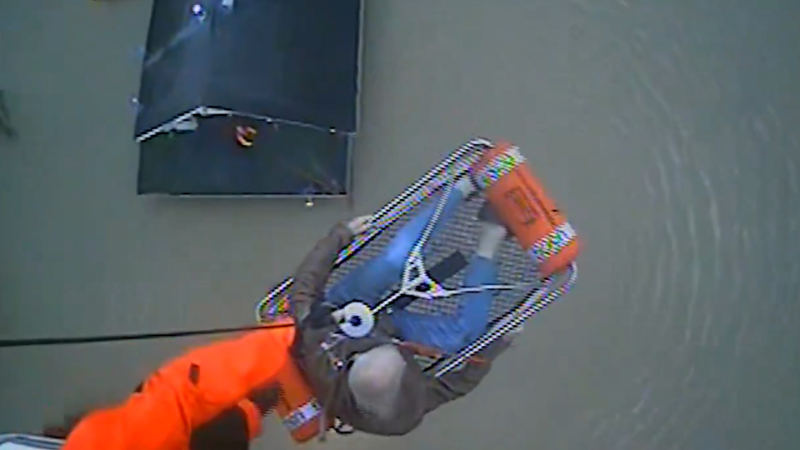

Skomal has been working on a population study for about five or six years, monitoring how the sharks move through Cape Cod. He and his team work in tandem with a plane that flies over the ocean to spot the shark from above. When they spot the shark, they prepare to tag it so that they are then able to monitor its location.

In this Sept. 13, 2012, photo, Massachusetts shark expert Greg Skomal, right, and expedition leader Chris Fischer discuss their success after tagging their first Atlantic great white shark on the research vessel Ocearch off the coast of Chatham, Mass. (AP Photo/Stephan Savoia)

Using the shark data provided by Skomal, Merchant analyzes the weather conditions against the sharks’ locations.

“Unfortunately, the data that I like to use is not available in real-time. And it's only posted in an archive once every month,” Merchant said. “For instance, I have to wait until the beginning of August to get all of July's data. So I mean, it's not ideal.”

The pair’s hypothesis is not an official study, but Merchant said he is working on two papers on the subject. A study with funding may allow the pair to use more precise instruments and real-time data to help better understand the relationship between sea breeze and shark attacks.

“We're getting more and more confident that this is happening all across the globe,” Merchant said.

While this is one of the first times scientists examined the relationship between sea breeze and shark attacks, this is not the first time that scientists looked out how weather impacts shark behavior. A study, led by Dr. Nicholas Payne, a visiting researcher at Queen’s University, published in March 2018 in the journal Global Change Biology looked at the water temperatures when tiger sharks are most abundant and active. Tiger sharks are the second deadliest species of shark, falling right behind the great white in recorded attacks on humans, according to the study’s press release.

The study also looked at how changing ocean currents and warmer waters may alter shark migratory patterns, bringing them closer to shore, and thus, increasing the possibility of attacks.

Report a Typo